No Holds Barred: Firstly, can you tell us about yourself?

Paul Cupitt: I’ve lived in Newcastle, New

South Wales, Australia, for most of my life. I also spent a bit of time in

Sydney. I got interested in boxing when I was younger; about the time of the

Holyfield-Tyson fight. It was just a sort of casual interest at that time and

grew much larger around the Tyson-Lewis fight and I’ve been a pretty hardcore

fan ever since then. I’ve worked in probably every role in boxing apart from

promoting since I became involved in the sport. I had an amateur career that

lasted about five or six years; I won the Australian amateur boxing league

title in 2012, turned pro about eighteen months later, had a couple of pro

fights. Haven’t fought for about four years now, but I wouldn’t say I’ve

retired just yet. I’m more of a trainer and historian now; I’ve been a member

of the International Boxing Research Organization for about three years. I

teach kids boxing at the local youth club; training at the grassroots level.

No

Holds Barred: You fought as an amateur for five or six years?

Paul Cupitt:

Yeah, on and off. I had my first fight in 2006 and my last one in about 2013.

There was about three years in there where I didn’t fight.

No

Holds Barred: So, you started quite late then?

Paul Cupitt: Yeah, I had my first fight just

before my twentieth birthday. My dad took me to the gym to let off a bit of

steam when I was a teenager. I sort of went from being a hardcore fan to

falling in love with the sport completely.

No

Holds Barred: Did you plan to be a professional fighter for longer or did you

just want to give it a try?

Paul Cupitt: I had planned to do more; my

career got side-tracked before it even started really. It’s very big on selling

tickets in Australia; I guess that’s the same everywhere. I had a lot of people

backing me when I first turned pro, but a couple of bad promotions where people

bought tickets and then the fights fell through, so the people stopped buying

tickets. It’s a hard sport when you haven’t got anyone with money behind you.

So, it just sort of fizzled out. I’m also quite injury prone.

No

Holds Barred: Now you train fighters?

Paul Cupitt: Yeah, I’ve helped out training

probably four or five pros. I help out with one guy at the moment, but he lives

quite a fair distance away. So, I sort of help corner him. I’m just trying to

be involved in the lower levels and groom them from the lower levels up now; I

think getting kids involved in boxing at a younger age makes a big difference.

No

Holds Barred: So, what made you choose to write a book about Jack Carroll?

Paul Cupitt: Well, I originally started the

project as a book on Ron Richards and Fred Henneberry, who were two Australian

middleweights that fought each other ten times. I’d just sort of run out of

things to read and wanted to read something on Australian boxing, and I knew

the story of those two; I knew about Carroll as well. Richards was an

Aboriginal boxer from Queensland, and Henneberry was a white, working class guy

from New South Wales, so it was like a natural rivalry; especially back in the

1930s. It was quite a heated rivalry: five of their ten fights ended in

disqualifications. I wrote about thirty-thousand words on them before I got to

Henneberry’s bouts with Carroll; just sort of reading about them - especially

the second and third fights where Carroll beat him - and just how much the Australian

people loved Carroll, made me switch the focus onto him. The stuff I wrote

about Richards and Henneberry stayed in the book because I felt it added to

Carroll’s legacy. I think Carroll isn’t just one of the unsung heroes of

Australian boxing, but also one of the unsung heroes of Australian sport. The other

big athlete at the time when Carroll was fighting was Sir Donald Bradman. I

mean, you’d probably know who Bradman was without even being Australian I think,

but nobody knows who Carroll is; he doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page, and I

think that’s a shame really because he was one of our greatest sportsman of the

time.

|

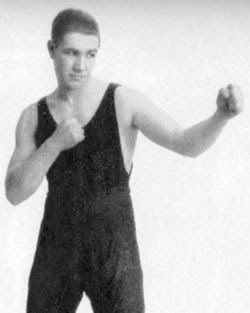

| Jack Carroll Owner: National Library of Australia |

No Holds Barred: Why did so many of Richards’ fights with Henneberry end in disqualification?

Paul Cupitt: I think one of the earlier ones

was a controversial one where Henneberry hit Richards in the back of the head; he

was actually on his way to winning by knockout in that fight. As for the later

ones, Henneberry was a businessman; he used to gamble large sums of money on

his fights, and back then in Australia if a fight ended in disqualification,

all bets were off. So, Henneberry had a habit if a fight wasn’t going his way;

he’d start using headbutts and his shoulder in the clinch. He’d bet his whole

purse on himself! Henneberry gets labelled as this dirty, racist fighter, but I

don’t think he was either. He was very much a businessman; he did what he had

to do to make money at a very tough time in the sport.

No

Holds Barred: I checked out Richards’ and Henneberry’s records. I saw that

Richards beat Gus Lesnevich and some other big names.

Paul Cupitt: Yeah, Richards battered Lesnevich!

He dropped him twice from memory, I think. One of his eyes was swollen shut at

the end of the fight; he battered him.

No

Holds Barred: Had you written any other books before your book on Carroll?

Paul Cupitt: No. When I went looking for

something to read on Australian boxing, I found there was nothing really

written in detail apart from the obvious ones like Les Darcy and Jeff Fenech,

and they were just overall history books on Australian boxing. But, this was

really our golden era; Australian boxing was at its peak when these guys were

fighting. So, one day I just sort of thought to myself, “how hard would it be

to write a book on this?”, and just started researching it. I then started

writing on the Richards-Henneberry rivalry. I’d written articles years ago, but

they weren’t very good. I’ve always had an interest in writing about boxing, which

I think comes from my reading habit. I’ve written a few articles in-between

writing my book, which I think helped my skills as a writer. But, this was my

first really big foray into writing.

No

Holds Barred: How did you compile your research? Did you get any help with

research, editing etc.?

Paul Cupitt: Harry Otty gave me some help; I

was put in contact with him through being a part of the IBRO. He helped me

format the book and get it out there. He basically gave me a crash course in self-publishing.

Harry Otty wrote the book on Charley Burley; it’s an excellent book! It was

actually the last book I read before I started working on my book, funnily

enough. Harry had a quick read through what I’d written and told me to change

this and change that. He helped me with things like how I had the dates set out

and stuff like that; stuff I hadn’t even thought about. So, he helped me with

the formatting of the book, which is a big deal because you get guys who charge

as much as $5,000 for that sort of stuff online.

No

Holds Barred: How long did it take you to write the book and how did you find

the time?

Paul Cupitt: I pretty much had to balance

writing with work. It was a four-year project; it was an on and off sort of

thing. I started out just doing an hour here and hour there. It was all over

the place; like I’d written bits about Henneberry and Richards, and then

started writing bits about Ambrose Palmer who was another great Australian

fighter at the time - he fought both Henneberry and Richards. He actually

bested both of them in their series; he was much larger than them though. His

most famous fight was probably against Young Stribling. Then, I started with

bits on Carroll and I found there were big holes in the middle of the whole

thing. Once I filled the gaps in and the book had its direction, I was working

a full-time job towards the end; I was up at 6am, and some days writing all

afternoon until midnight. My schedule depended on when my wife was working too

so I wasn’t neglecting her too much.

No

Holds Barred: I read he was born Arthur Ernest Hardwick. Where did the name

Jack Carroll come from?

Paul Cupitt: It was actually the birth name of

one of the biggest stars in Melbourne at the time: Charlie Ring. Hardwick took

the name Carroll so his mum wouldn’t find out he was boxing! Ring was actually

at the first fight that Hardwick fought as Carroll; Ring looked on the bout

sheet and saw his birth name on it and walked up to the person they said was

Jack Carroll and said, “if you disgrace my name, I’ll disgrace you!”. So that

was Jack Carroll’s first memory of his first fight; having a former Australian

champion threaten him if he didn’t do well!

No

Holds Barred: So, Charlie Ring was pretty decent too?

Paul Cupitt: Yeah, he was a former Australian

middleweight champion; I think he lost the title in 1922. He was one of the

biggest stars in Melbourne at the time Hardwick turned pro. He relocated to

Britain, but not too sure how he did over there.

No

Holds Barred: How famous was Carroll during his prime?

|

| Jack Carroll & Don Bradman Owner: National Library of Australia |

Paul Cupitt: Well, the only bigger athlete at

the time in Australia was Don Bradman. The thing with Carroll was he hated the

limelight, so he didn’t like people fussing over him; which is sort of why he

was forgotten after he retired. His fight with Izzy Jannazzo was held in front

of more than thirty thousand people. The first fight with Bep van Klaveren

would have drawn more if it hadn’t rained; people were pulling things out of

bins to shelter themselves because they wanted to stay there and watch him.

That’s how much they loved him at that point!

No

Holds Barred: Are Australians that averse to rain? In the UK, we’re so used to

it, I don’t think anybody would really care if it rained [laughs].

Paul Cupitt: Well, it was in the middle of the

summer and we get that real tropical, heavy rain here. This rainstorm

apparently just came out of nowhere; it started raining just before eight

o’clock and the fight was due to start at about eight thirty, so people were

pulling bits out of bins and shielding themselves with things they found under

the seats. They were just standing there with these makeshift covers and

watching these two fight in a torrential downpour.

No

Holds Barred: Was the ring not even covered?

Paul Cupitt: Well, it was on Boxing Day in the

middle of the Australian summer, so they weren’t expecting rain. It was the

promoter’s first open-air venture, so they were still doing things on the fly.

They had a shelter set up in case it rained in the second fight though.

No

Holds Barred: Could you describe Carroll’s fighting style?

|

| Jack Carroll Owner: National Library of Australia |

Paul Cupitt: Well, there’s only four minutes

of footage of his entire career. There are bits from his third fight with

Henneberry, and the rest are from fights later in his career. I took a lot of

footage from VCRs, and just sort of put it all together for YouTube. I think

he’s often incorrectly labelled as a classy boxer; sort of in the stick and

move type style. He was actually more of a wild-man who imposed his will on a

lot of his opponents. I think the big thing that’s undeniable about his style

was his work-rate and his speed; a lot of guys just couldn’t handle the sheer

volume of the leather he threw at them. He was often cruising through fights

behind his jab until the other guy nailed him, at which point he just started

unloading on them. He was famous for his left hand; you’d rarely read about him

using his right hand. He threw every punch with it; he would throw hooks and

uppercuts up close; he threw it well to the body. His trainer, Bill O’Brien,

helped him develop the great jab which complemented his height; he was just under

one hundred and eighty centimetres tall, which is huge for a welterweight. From

what I’ve seen of footage, the only modern-day guy he kind of reminds me of is

Paul Williams; the way he used his size and style, and bombarding guys both at

range and on the inside.

No

Holds Barred: Was Bill O’Brien a renown trainer?

Paul Cupitt: Carroll was his main charge; he

didn’t really have anyone else as big as Carroll. He had a couple of other guys

like Jack McNamee, who was a good fighter. There were a lot of really good

trainers in Australia at the time; Ambrose Palmer became Johnny Famechon’s

trainer, and Jack Carroll became a trainer for about ten years after he

retired. Palmer and Carroll never fought each other professionally, but they

often cornered against each other later in their careers. Palmer’s dad was

friends with Peter Jackson, and before Jackson died, they’d been working

together on the ultimate method of boxing which they called ‘the Method’.

Palmer’s dad taught Ambrose and all of his brothers how to fight using the

‘Method’, which was a very sort of defensive style of boxing focusing on defence

and using mainly the left hand, and just waiting for the opening for the right

hand. So, there were a lot of good trainers in Australia at the time; Bill

O’Brien was one of the more underrated ones. He was also a full-time barber, so

he didn’t really have the means to get around with his fighters; so, I think a

lot of guys left him. That’s the impression I got from the research, but I

couldn’t really find the evidence to be sure.

No

Holds Barred: Did Carroll have much of an amateur career?

Paul Cupitt: No. A lot of guys just turned pro

early on to make extra money at the time. He used to spar his friends at school

and stuff like that, but nothing official.

No

Holds Barred: Amateur boxing doesn’t seem as big back then as it is in modern

times.

Paul Cupitt: Especially in Australia. We had

some good Olympians like Snowy Baker, who I think was one of the few

Australians who won an Olympic medal. I don’t think he ever fought

professionally though. He played rugby union and swam; he was a multi-sport

athlete. He ended up being one of Les Darcy’s promoters; he even promoted on

the West Coast of America towards the end of his life. There wasn’t much of an

amateur system in Australia at the time; a lot of guys just turned pro young,

like Carroll who turned pro at seventeen.

No

Holds Barred: He began his pro career at bantamweight, before moving up to lightweight,

and then welterweight soon after. What made him transition through weight

classes in such a small period of time?

Paul Cupitt: I think it was just because of

the young age he turned pro. It was customary in Australia at the time to have

a 2pm weigh-in, so it wasn’t like guys were cutting a lot of weight. Being

almost one hundred eighty centimetres tall, it didn’t take long for him to fill

out from being a boy to a man. So, I think he just naturally put the weight on.

He turned pro at seventeen and I’d say he was a fully formed welterweight by

about twenty-one. He won the title when he was twenty-two, I think. I met some

of his family a few weeks ago; his grandson showed me a photo they had which

I’d never seen before. Most of the photos you see of him are of him in his late

twenties/early thirties, but in this one he couldn’t have been twenty years old;

full set of blonde hair; a beautiful photo.

No

Holds Barred: He won the Australian welterweight title in 1928 against the

British-born Al Bourke via seventh round stoppage. How big a deal was his win

in Australia at the time?

Paul Cupitt: Being Australian champion in the

1920s/30s was quite a big deal. It’s not like nowadays where Australian guys

can bypass national honours and fight for IBF Pan-Pacific and WBA Oceania

titles. You had to win the Australian title before being able to fight for the

Empire title, which was the next one up. So, you had to prove you were the best

in Australia first. With there only being eight weight classes at the time, and

with boxing being as popular as it was back then, being one of the eight

champions in Australia meant everyone knew who you were.

No

Holds Barred: So, being Australian champion back then was a bit like being

British or European champion back in the day?

Paul Cupitt: It wasn’t as big as being

European champion, but being Australian champion was definitely a big deal.

Guys would come from America, Britain, Canada and other countries to fight the

Australian champion because they knew they could make a lot of money.

No

Holds Barred: How popular was boxing in Australia at the time?

Paul Cupitt: Oh, boxing was huge during that

era! It was already huge before Carroll started. It’s surprising to hear now,

but when Carroll was at his best boxing was bigger than cricket and rugby

league. The only sport that was bigger than boxing at the time was horse

racing. With Australia being a Mecca of boxing before the First World War - Bob

Fitzsimmons started his pro career here, Jack Johnson, Sam Langford, Sam McVea

all toured Australia - and prior to the Walker Law being passed in America,

many American fighters came to Australia because we had such a solid system in

place; fights were scheduled for 20-rounds, they were scored, large crowds

attended, and there were no issues with the police or anything like that. But, after

Les Darcy died the popularity dropped off. It came back first with Henneberry

and Palmer and then later with Carroll and Richards.

No

Holds Barred: Carroll lost the title to Charlie Purdy later in 1928 via

disqualification in what appears to have been a non-title fight. Why did the

title change hands, and why did Carroll not protest?

Paul Cupitt: Well, it’s an interesting one.

Purdy sort of claimed the title, but Carroll was still recognised as the

champion by the major stadiums because he hadn’t lost under championship

conditions. Because there wasn’t a rematch, both men kept their claim to the

title. Then, Purdy lost the title to Wally Hancock who was signed to Leichhardt

Stadium - which was the rival to Sydney Stadium - meaning that Carroll couldn’t

fight Hancock, so it was pretty much like the politics around today. Carroll

eventually beat ‘Bluey’ Jones and that reunified the titles, but he never

officially lost it, at least in the eyes of Stadiums Limited who ran boxing in

the major stadiums at the time. Purdy was one of his main sparring partners

later in his career.

No

Holds Barred: So, was it a bit like Carroll was still considered the champion

but Purdy held the title?

Paul Cupitt: No, it was sort of the other way

around. Carroll still held the title, but a lot of people considered Purdy the

champion. There hadn’t actually been an agreement for the title to be on the

line, but because they both made the weight, Purdy claimed that he was the new

champion. The public didn’t really warm to Carroll until he beat Henneberry in

the rematch. So, when Purdy claimed he was the champion, a lot of the crowds just

sort of went with it. It was just because Carroll was so dominant. He didn’t

really look like a boxer - he was described as having ‘lolly pink skin’, I

think the term is; blonde hair, tall and lanky, just not your stereotypical

muscle-head boxer. That sort of turned the crowds against him early on, but as

he started beating all of these guys, he won the crowds over eventually.

No

Holds Barred: He fought a lot of boxers who some readers may not be familiar

with. Could you tell us about some of his more famous opponents? What made them

stand out from the rest?

|

| Jack Carroll & Tod Morgan |

Paul Cupitt: Well, starting with the world

ranked guys: his biggest win was probably against Bep van Klaveren; he was the

number one welterweight contender when Carroll beat him. He was also an Olympic

gold medallist. He’d beaten some good fighters leading up to the fight like Kid

Azteca and Ceferino Garcia. He was robbed against Young Corbett, although he

was beaten fairly in the rematch. At the time, he was being groomed to fight

welterweights Jimmy McLarnin or Barney Ross for the world title. But, he took a

huge money offer to fight Carroll, who nobody in America had heard of at the

time. Carroll won almost every round in both of their fights; those fights sort

of catapulted Carroll to the top of the rankings. Wesley Ramey was another big

win; he was the number one contender at lightweight and is often considered one

the greatest fighters to never win a world title. He’d beaten Tony Canzoneri

not long before he came to Australia. Although Carroll was a lot bigger than

Ramey; Carroll was a huge welterweight whereas Ramey was an average-sized

lightweight. Richards and Henneberry were both at some point ranked in the top

five at middleweight in the world, and Carroll beat them both easily. Tod

Morgan was a former super-featherweight world champion; he made around ten

defences of that title. He also beat guys like Jack Portney and Willard Brown, who

were top five welterweight contenders. I don’t think some people today realise

how big a deal that is; at that time, there were four times as many

professional boxers and there weren’t all the multiple sanctioning bodies.

Nowadays, if you’re a top five contender, you’re really in the top twenty

boxers in your division. There were also less weight classes, so being ranked

in the top five back then was probably harder than actually winning a world

title today.

No Holds Barred: Also, a lot of people today don’t realise that losses were much less damaging to a career than they are today. Also, a lot of fighters back then sparred much less than today, so a lot of fights back then could perhaps be described as competitive sparring sessions.

Paul Cupitt: Yeah, exactly. Also, you had guys

fighting back then with broken hands and cuts still healing from a fight two

weeks before. As long as they put on a good show, the crowd would keep coming

back; a hard-fought loss was sometimes better than a win where you didn’t look

too good.

No

Holds Barred: Some fights back then were declared ‘No Contests’ if the referee

deemed the fighters hadn’t made enough effort.

Paul Cupitt: Carroll had a couple of those; one

of the last blemishes on his record was the fight before he fought van Klaveren.

He fought a fighter called Paul Schaeffer. The newspapers gave this big

promotion on Schaeffer, who was the British or Canadian champion - he was sort

of half British, half Canadian - and when they came out, Carroll just murdered

him to the point where the referee had had enough, but instead of stopping the

fight and declaring Carroll the winner, he called it a No Contest. Carroll got

paid but they didn’t pay Schaeffer. That was actually Carroll’s last fight at

Sydney Stadium; after that he signed for a new promoter who was previously working

at Sydney Stadium but wanted to start an open-air venture, and that sort of led

to the van Klaveren fights and Carroll’s legacy as Australia’s greatest

drawcard.

No

Holds Barred: He also fought many opponents several times, such as Fred

Henneberry, Roy Stewart, Jack Smith, Harry Casey, Charlie Purdy, Jimmy Leto,

and several others. Are these renown rivalries in Australia in the same way

Jack Britton vs Ted ‘Kid’ Lewis or Muhammad Ali vs Joe Frazier are in the UK

and USA?

Paul Cupitt: Not so much with all of those

names. There was a huge rivalry between Carroll and Henneberry. With those

other guys, Australian boxing sort of had some really top guys and some much

lower guys, and the guys in the middle sort of had to fight each other quite a

few times, and if it was a good fight the promoters were quick to put it on

again the following week if both fighters were still good to fight again.

Henneberry’s rivalries with Richards and Palmer were by far fiercer rivalries

than those with Carroll; I think that’s probably more to do with Carroll being

pretty much peerless in Australia at the time. Palmer was the Australian

heavyweight and light-heavyweight champion at the time, and he wouldn’t put the

titles on the line against Carroll because he knew it was a fight he wasn’t

guaranteed to win; Carroll chased the fight with Palmer for a year.

No

Holds Barred: He wanted to fight Palmer at light-heavyweight?!

Paul Cupitt: He wanted to fight him for the

heavyweight title! He was willing to fight him at any weight. Palmer fought

Young Stribling with a fifteen pounds weight disadvantage, yet he wouldn’t

fight Carroll with a twenty pounds weight advantage! They sparred a fair bit, so

he knew Carroll wouldn’t be an easy fight. Carroll and Palmer were the two best

guys in Australia at the time, so even though there was such a size

disadvantage for Carroll, he wanted that fight because it was the biggest money

fight for him at the time.

No

Holds Barred: So, Carroll and Palmer were the two biggest names at that time?

|

| Ambrose Palmer Owner: Boxrec |

Paul Cupitt: Yeah, at that time they were.

Henneberry was still working his way up. His stock dropped a bit after Carroll

beat him, and Richards’ stock dropped a bit after Henneberry beat him in their

third fight. It wasn’t until his [Richards’] bouts with Deacon Leo Kelly, who

was a world rated light-heavyweight at the time, that he became a really big

star in Australia.

No

Holds Barred: Carroll was knocked out by the heavier and future Australian

middleweight champion Fred Henneberry in the thirteenth round of their first

fight in February 1932. Was he close to victory prior to the knockout?

|

| Jack Carroll & Fred Henneberry Owner: National Library of Australia |

Paul Cupitt: He was winning that fight easily

for the first ten rounds. He had a hand injury which had been plaguing him for

a bit leading up to that fight, so he was ring rusty. His daughter had just

been born too, so his match fitness wasn’t at the level it normally was. But,

he was well ahead after ten rounds, then he got tired and Henneberry had just

sort of found his groove as a fifteen-round fighter and just took over in the

last couple of rounds. Carroll took the ten-count, but the fatigue had set in.

Henneberry just sort of battered him to the ground and Carroll was just too

tired to get up. All the reports of the fight were talking of Carroll

dominating the fight and then becoming exhausted and Henneberry getting

stronger and stronger and eventually cornering him, putting him down, and him

not being able to get up.

No

Holds Barred: He later defeated Henneberry twice on points, again outweighed

both times. How significant were those wins?

Paul Cupitt: They were huge. The second fight

was one of Carroll’s first fights in a long time in front of his hometown fans.

Henneberry refused to put the title on the line because he knew he wasn’t

guaranteed to retain it, so he refused to weigh in leading up to the second

fight. Carroll then beat him to a pulp; he swelled both of his eyes shut.

Outside of his second fight with van Klaveren, it was probably his finest

display in the ring. There were constant delays for the third fight; Henneberry

had boils on his shoulder, I think, and Carroll came down with the flu, so the

date changed a few times. Then, Henneberry pulled the same stunt again and refused

to put the title on the line; he weighed in this time, but he wouldn’t put the

title on the line. It ended up being the same situation that Carroll had with

Purdy but reversed. So, Carroll was claiming the middleweight title but

Henneberry was still considered the champion. Then, Hugh McIntosh became

involved again in boxing in Australia and basically said, “Henneberry’s the

middleweight champion and Carroll’s the welterweight champion” and just sort of

left it at that, so Carroll stopped trying for the middleweight title.

Check out PART TWO of this exclusive interview with Paul Cupitt tomorrow.

No comments:

Post a Comment